| Disclosure: The links on this page are "Affiliate Links" and while these are shown at no costs to our viewers, they generate commissions for our website(s) |

When it comes to art, taste can be an individual thing, and this concept is noted in the variety of genres of music, movies, books, etc. that people experience. Each representation of those categories could come with people who are strong fans as well as those who think it’s terrible. For evidence, look at science fiction. Some people are fanatics, but others seem to look down at it—passionately.

While this lack of appreciation toward science fiction could be based on preferences, sometimes the qualms we have with artistic works go deeper than simply not enjoying it. What might be stranger to note is that those moments of deep dislike can even be linked to something as innocent as children’s books.

This is where you’ll find me, griping about how one of the most embraced children’s stories is a terrible tale to impart to children. Specifically, this book that earns my disapproval is one you’ve probably already heard of, and one you might have considered buying a child in your life for a random surprise or gift.

That book is The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein, and if you find yourself picking up a copy for a child’s birthday present, carefully place it back on the shelf and walk away.

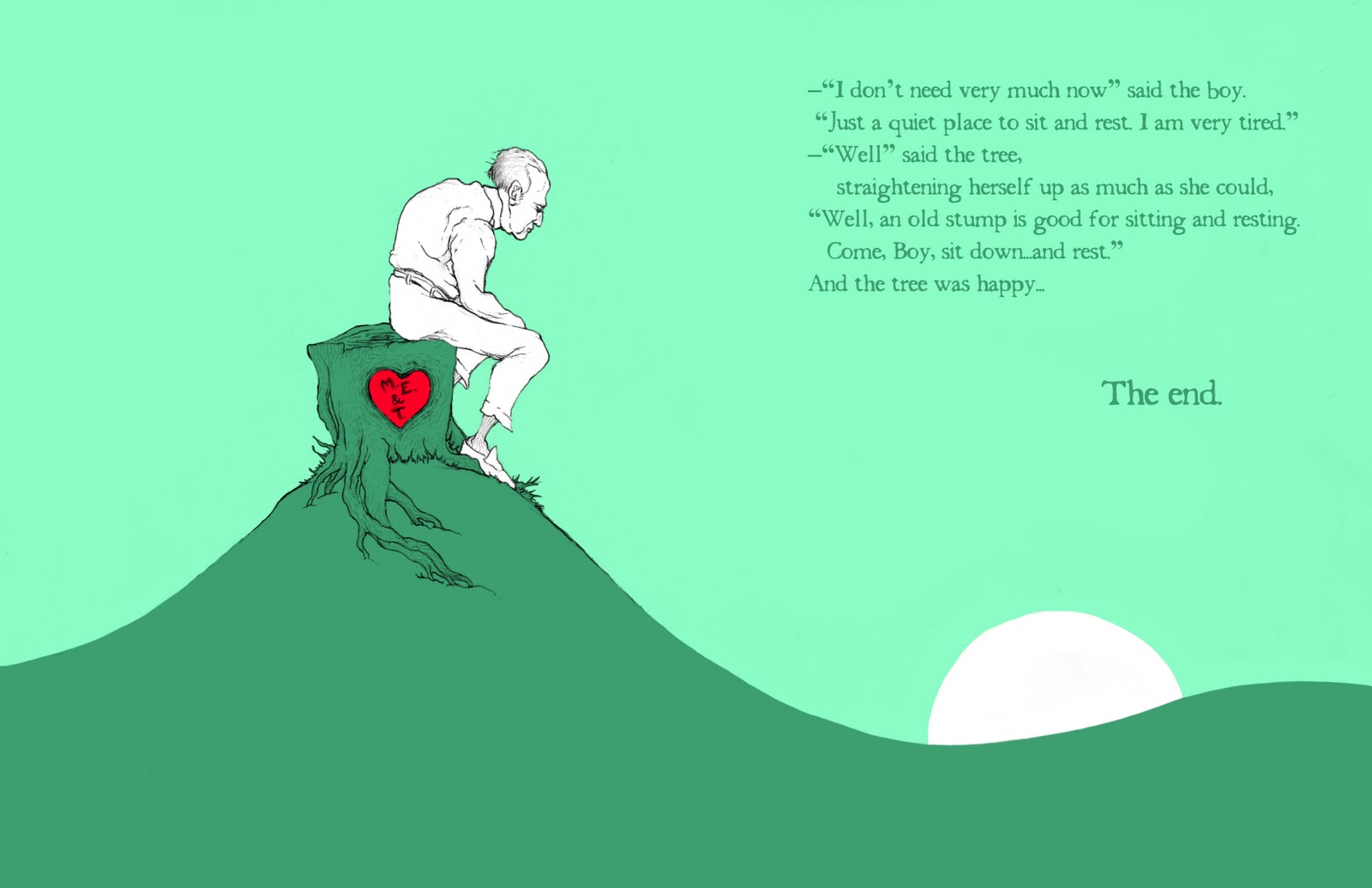

An obvious reason for this leave-it-be approach has to do with the level of sadness that occurs at the book’s end. For those of you who may not know, the story concludes with an old man sitting on a sentient tree stump. Essentially, both have grown old and used, and the book wraps up with the idea that while the tree is glad to have the older fellow in his life, both tree and person are too worn to be as active as they used to be.

No doubt, aging and mortality are real concepts in life, but bear in mind that the targeted age group for this book begins at just four years old, according to the book’s Amazon page ( https://www.amazon.com/Giving-Tree-Shel-Silverstein-ebook/dp/B00DB2QZPI/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1515676398&sr=8-1&keywords=the+giving+tree ). This is the age where children should be considered on a careful level about what they can and can’t handle, and while a four-year-old might understand this person and tree have aged, the process could be too large to grasp to its full extent because the child reading the story is so young. Worse, that child could manage to wrap their mind around the concept to understand that they’re essentially reading an end-of-life story for this man and the mistreated tree.

Either way, children are dealt a heavy burden with the adult concepts at play in the final lines of this book, and they might not have the mental tools to successfully work through those issues. Undoubtedly, if a loved one deals with illness or passes on, that child could be exposed to relatable dilemmas, but if that exposure doesn’t need to happen—if that detail of childhood innocence can remain intact until the child grows older—no book needs to be the reason why they have to let go of that part of their youth.

You might be thinking that Old Yeller , Where the Red Fern Grows, and Bambi have these kinds of undertones. I would argue the first two of those listed tales are not the best choices for your child on a similar level of reasoning, and that Bambi does not address mortality as a main focal point. His mom’s death is one detail in the movie—not the final visual.

If you aren’t convinced this mortality is a reason to not give The Giving Tree to a child, the most pressing reason is still to come. That reason is, in spite of any insistence that this is a morally strong book about selflessness, the truth is this story is a representation of selfishness at its finest. The rationale for the difference of opinion—selfishness vs. selflessness—rests in people looking toward different characters to come to their decision.

If a reader focuses on the tree, the tree does give and give while asking for little to nothing in return. It can’t even be argued that the tree is only doing these things because it wants to spend time with the boy since the tree allows the boy to cut it down to construct transportation so the boy can leave. Since the name of the book is The Giving Tree , this fixation on the tree would make sense, but let’s consider that a child might relate to and understand a person as something more similar to them. With that frame of mind, it’s not absurd to suspect a young child reading this book would focus on the person’s actions rather than the tree’s, and that’s where the astonishing level of selfishness surfaces.

The book begins when the boy is young and playing with the tree, and both enjoy the time and company. This is a true, remarkable friendship between the two, but as soon as the playtime no longer suits the child’s interests, he nearly abandons the tree to the point where he only shows up if he needs something—like items to sale or lumber.

This becomes the standard pattern for the book. The tree misses the child and wants to play every time the child comes near, but the child tells the tree what he wants, gets something, and leaves—only to come back when he needs something else.

If a child reading this book were looking toward the boy growing into a man as the relatable character, that child could be learning horrible behavior. He is being taught to take his friends for granted since there is no evidence the child in the story makes the tree a part of his life beyond these appearances where he gets things from the tree. The tree only matters, no matter how true their relationship had been in earlier years, when it can offer something beyond companionship and comradery, and this is a horrible value to instill in a child.

The level of ingratitude from the story’s human character is striking as well since he never thanks the tree for its assistance, even though he is literally tearing the tree into nothing beyond a stump. The tree is becoming pieces in front of him, and rather than recognize this as a sign that he should probably stop—that his friend, the tree, has the right be okay as well—he keeps pushing for more. There is no hesitation in the human’s requests, although the tree is suffering so greatly for the process, and there’s little to no reciprocation happening on any level. The tree gives, but the boy does not give anything but a momentary conversation of his problems in return. The tree only finds joy when the boy has joy, but the boy shows no indication that he cares if the tree is joyful or not. It truly is all about the boy.

This teaches a child disrespect, disregard, and selfishness, and it shows them that no matter how horrible circumstances are for another person—or tree, in this case—it’s okay to not acknowledge their problems while you focus on your own.

Let’s say, however, that the child does fixate on the tree as the relatable character in the story. Yes, that tree does give and give, but not in a healthy way. What the tree has done is let what was supposed to be a friend take away every ounce of its being besides the tiny stump of a character that remains. While giving is great in the right context, teaching children that destroying their own livelihood for the sake of pouring into someone who does not appreciate the help—or need it, potentially, since there’s no indication that the boy tried get these things on his own before having the tree hand them over—is again a questionable moral to instill. In essence, it’s preparing children to be a part of unbalanced, unhealthy relationships by praising the tree that has endured so much abuse over the years with too little thought for itself.

In either direction, this book portrays characteristics and behaviors that should be thought over before handing the book to a young child. Do you want your child to be selfish like the boy or ill-used and ruined like the tree? If not, shuffle over to another shelf to find the child in your life a better book for their gift.

Reference

Silverstein, S. (1964). The Giving Tree . Retrieved from http://schools.nyc.gov/NR/rdonlyres/35C1809B-B30D-...

![TLC Zoombinis 3rd Grade Learning System (PC & Mac) [Old Version]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/61l60-7bGuL.jpg)